Extracts from January 14, 2017 issue

George Michael had two strong recurring premonitions. The first was that he’d be famous. The second was that he’d die young.

“From a really early age, I believed I was going to be a star,” he told me when I interviewed him at length in 1986. “I remember being on a bus when I was a child, about 8 or 9. I’d had a bad day at school I’d been picked on and I remember thinking it would be OK when I was older, because I wasn’t going to be like everybody else. That’s the reason kids want to be stars. They think they’ll be able to rise above their problems because they’re famous which obviously isn’t true.”

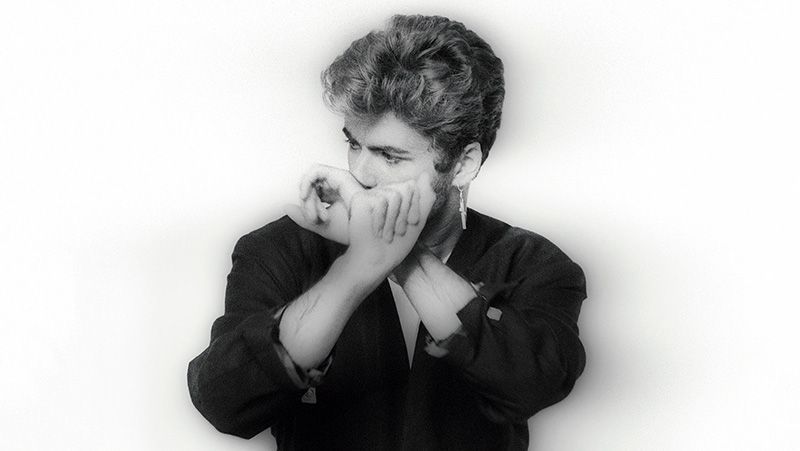

Michael, who died at home in Oxfordshire, England, at the age of 53 on Christmas Day, had enduring faith in his talent. But one of the most striking things about him was the discrepancy between the poised, clever sex symbol I was talking to and his accounts of growing up outside London. “People have no comprehension of what I looked like as a kid,” he said, laughing. “I was such an ugly little bastard.”

Even when fans were swooning over him, he remembered being an overweight kid who wore glasses. “He never thought he was good-looking,” Rob Kahane tells Billboard. Kahane managed the singer at the height of his solo stardom. “When he looked in the mirror, he’d still see a pudgy, homely kid.”

Like a lot of disenchanted preteens, Michael took solace in the escapism of pop music, and he obsessively studied how hit songs were arranged. He loved pop so dearly, he turned himself into its embodiment, and an unashamed advocate of its merits. “You either see pop music as a contemporary art form or you don’t,” he said. “I do, very strongly. It’s the only day-to-day, moving art form.”

Wham!, the duo he formed with childhood friend Andrew Ridgeley, was outrageously, blindingly pop: Their hits had quick tempos, upbeat hooks and peppy videos of the duo, often in shorts or cropped T-shirts. Michael once described them as “f***off pop songs people can’t resist.”

Wham! had everything but respect one writer called them “two unsophisticated con men” so Michael split from Ridgeley. He dueted with Aretha Franklin and Stevie Wonder. He wrote, arranged and produced 1987’s Faith; the album sold 25 million copies worldwide and 10 million in the United States, where four of its singles went to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, leading to a Grammy for album of the year. Michael, certain he would lose to Tracy Chapman or Sting, didn’t attend. (Kahane, who teased the singer like he was a little brother, called him and said, “Listen, idiot, you won.”) Michael made all the music decisions, and all the business decisions, too. “Being a control freak is f***ing exhausting,” he told me. “It took me about two months to suss out that the music business was full of assholes, and I knew better than they did. That’s when I dug my heels in.”

A lot of heel-digging followed. By the time Faith started to fade, “I felt like I was going insane,” he later said. Michael thought his renown as a sex symbol stopped people from giving his music the respect it deserved. So in 1990, before he released Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1, he planned a severe change: no interviews, no tours and no appearances in his own videos. In the famous clip for “Freedom! ’90,” starring five supermodels, Michael literally destroyed a guitar, jukebox and leather jacket, each a key element of his “Faith” video. “George was a very difficult person to manage — not because of his personality but because of his belief system,” says Kahane.

Kahane hated Michael’s plan, but Michael’s U.S. label hated it more. Don Ienner, who was president of Columbia Records, explains: “Clearly, I was concerned that George didn’t want to promote the album, tour behind it or star in his own videos, all of which had made him, deservedly, one of the most important stars in the world. If that was his vision, then we’d support it, but I thought there was a more elegant way to quiet the frenzy that was making him uncomfortable. Why announce that he wasn’t supporting the album, instead of being quiet and letting the music speak for itself? And when he blew up the guitar, the jukebox and the jacket, I felt it could offend fans who loved those images.”

At one point, according to subsequent court testimony, Michael overheard an argument between Kahane and Ienner, who allegedly referred to the singer as “that faggot client of yours.” (“It’s a silly accusation, and it’s untrue,” Ienner told me.)

“That was the trigger that set George off,” says Kahane. The singer went to court to dissolve his contract, which he ridiculously likened to slavery. “It was a moral issue,” he later said. He lost the lawsuit, which cost him about 30 million British pounds and kept him away from recording and touring for three years. “He was stubborn,” adds Kahane. “But that’s also why he performed at so many benefits he had principles.”

In the midst of the Sony lawsuit, Michael’s partner of two years, Anselmo Feleppa, died of an AIDS-related brain hemorrhage. “When he lost Anselmo, I thought he was going to do something bad to himself. I had people stay with him,” says Kahane. Michael came out to his family. Soon after, his mother, with whom he was very close, told him she had terminal cancer.

Michael later said he was clinically depressed during that period. Sometimes Kahane’s sister would read the singer’s tarot cards. “He was obsessed with saying, ‘I know I’m going to die young,’” recalls Kahane. “He’d say, ‘It’s OK. I’ve had a great life.’”

DreamWorks Records paid a hefty fee to buy his contract from Sony, and he released Older in 1996. It sold well worldwide but flopped in the United States. “George delivered us a completely finished album package, which is unusual. He understood how to use videos and photos in a way few people did,” says Robin Sloane, head of creative services at Geffen Records. But the images he picked were “somber, moody, mournful. It was over the heads of MTV viewers. People wanted the other George Michael.”

In 1998, he was arrested for “engaging in a lewd act” with an undercover policeman in a Beverly Hills park. Michael felt his fans already understood that he was gay. “He said it was everywhere in his lyrics,” recalls Bryn Bridenthal, who was head of publicity at Geffen. But he agreed to an interview on CNN so he could come out formally. “He had a sense of humor about it and wasn’t defensive. He did charming really well,” says Bridenthal.

Unlike his contemporaries Michael Jackson, Madonna, even Prince, to an extent Michael stopped trying to make hits. He released only two albums in his final 20 years: an album of mostly standards, sung with an orchestra, in 1999, and 2004’s Patience, on Sony Music, where again he worked with Ienner, who was now chairman and CEO. Michael’s music was chilly, thoughtful and rarely celebratory. When he made headlines in the last 10 years, it was for personal problems: a near-fatal case of pneumonia that forced him to cancel a 2011 tour of Europe, or drug arrests, or a car accident while driving under the influence, which led to a four-week jail stint.

In early December 2016, when Kahane was in London, a mutual friend encouraged him to reach out to Michael, who had recently finished 18 months in a Swiss rehab facility. “I called him, and he said, ‘I’m good.’ He sounded fine,” says Kahane. Though the two hadn’t talked in years, they made a plan to have lunch in January. And Kahane heard a few of Michael’s new songs, which he says are “totally pop, like something that would’ve been on Faith. The songs weren’t depressing. That’s why I thought everything was OK with him.”

Michael was intermittently active on Twitter, and in April 2014 he told fans he’d been watching video of his 2011 tour. “I saw the luckiest man on earth. So much love given to one man,” he wrote. “If only I had known, way back then, I’d have been one seriously happy kid. I love you.”

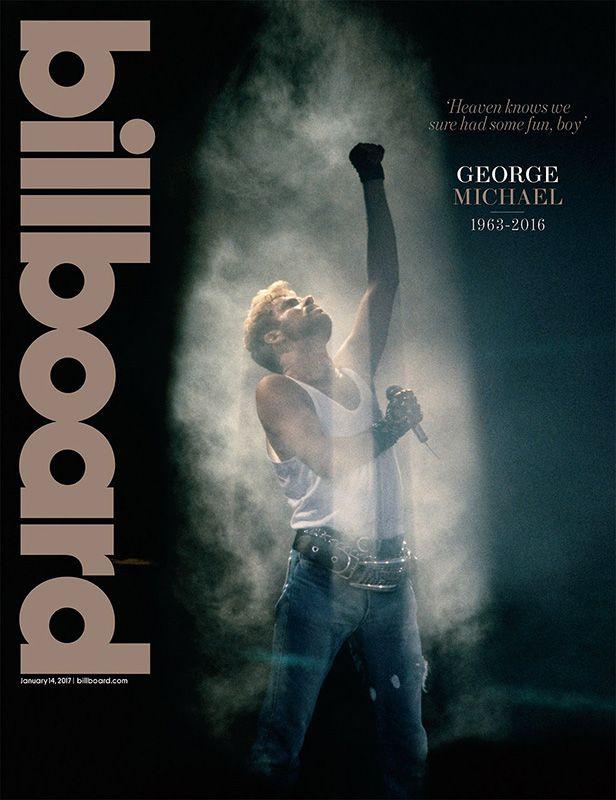

The Live Aid concert at London’s Wembley Stadium on July 13, 1985, was, among other things, a time capsule of British pop at its imperial peak. It fell during a heady era when the entire bill could be British (or, in the case of U2 and Bob Geldof, Irish) without seeming parochial.

The evening’s lineup featured three rejuvenated giants of the 1970s David Bowie, Elton John and Queen and, for one song only, a young gun who had absorbed lessons from them all. Midway through John’s set, the singer introduced George Michael, “this guy I admire very much,” and let him run away with “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me.”

Michael was modeling the riff on young American manhood that he would make iconic with 1987’s Faith – blue jeans, black leather jacket, sunglasses, stubble – while Andrew Ridgeley, his junior partner in Wham!, already looked dispensable. Unfairly tagged as good-time lightweights, Wham! had everything but credibility, and Michael’s performance made it clear that the 22-year-old was hungry to correct that. Before Faith, before even his duet with Aretha Franklin (also in 1987), Michael was overtly aligning himself with the greats, and he began with John.

“George was nervous as hell. The feeling was, could he deliver in this company?” says Bernard Doherty, the publicist for Live Aid. “Backstage they were laughing and joking: two local lads who came from down the road.” At that point, Michael, John and Freddie Mercury constituted an MTV-enabled troika of British megastars roughly-equivalent to the American triumvirate of Prince, Madonna and Michael Jackson.

Michael was a generation younger than John and Mercury, but he felt older than his years and bigger than the ’80s zeitgeist. “I’ve always felt that my talents were very traditional. I didn’t feel I was tied to youth culture,” he told me in 2004. Of his contemporaries, he added: “I always believed I would outlast everyone, with the possible exception of Madonna.”

Like his British heroes-turned-peers, Michael was a closeted gay man from the London suburbs whose voracious ambition was that of the conflicted outsider storming the citadel. Also like them, he was a versatile populist with a big-picture understanding of pop, a gift for universal melodies and a supernova showmanship that extended all the way to the cheap seats. For Michael, the success of the more flamboyant Mercury and John in the straight world was inspirational.

This was the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell era of pop, when stars scrambled norms of gender and sexuality in a way that bypassed homophobia while hitting a demographic sweet spot that excluded no one. “They acted out fantasies on behalf of their audience, but it was unthreatening, in the realm of make-believe rather than the truth of their sexuality,” says Martin Aston, author of Breaking Down the Walls of Heartache: How Music Came Out.

Michael made his affinity with his forerunners explicit in 1992, when “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me,” recorded live with John, became his last No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100. (Performing the song in Las Vegas three days after Michael’s death, an emotional John said: “I only wish George was here to sing it with me.”) Also in ’92, Michael gave a bravura rendition of “Somebody to Love” with the surviving members of Queen at the Mercury tribute concert. “It was probably the proudest moment of my career because it was me living out a childhood fantasy,” he said later.

Two things set Michael apart from his elders. One was his readiness for stardom: He wrote “Careless Whisper” when he was just 17 and waited three years until the time was right to unveil it. The other was his auteurdom: he was his own songwriter, producer, arranger, image-maker and strategist. Faith mastered and tweaked American forms for maximum pleasure, from the brisk rockabilly of the title track to the erotic manifesto “I Want Your Sex (Parts I and II),” from the deep soul balladry of “One More Try” to the sexual-spiritual alloy of “Father Figure.” This was something-for-everyone pop born of generosity rather than calculation, and it was irresistible. En route to winning a Grammy for album of the year, Faith produced four No. 1s on the Hot 100 and topped the Billboard 200 for 12 weeks. A young British solo artist wouldn’t reach that position again until Adele did 24 years later.

It was not for want of trying. Robbie Williams, the straightest camp man in ’90s British pop, modeled himself on Michael, but he was one of many British exports whose appeal didn’t translate to America. Michael appeared to have blazed a trail, but it was one that only he could travel down. “I’ve seen people aspiring to be me for the last 20 years,” he said in 2004, “and what they normally don’t understand is that to be me you’ve got to do the whole process.”

That was part of it – but the industry changed, too. Pop’s monoculture splintered into hip-hop, R&B, grunge and country, often reasserting traditional gender roles in the process, and saw off the kind of ecumenical megastar who straddled genres and demographics, especially the British variety. Just a few years after Live Aid’s summit meeting, the sun had set on British pop’s imperial phase, making Faith both its zenith and its last hurrah.

I was there at the High Court in London in 1993, the day George Michael testified in his lawsuit against Sony, in which he sought to be released from his recording contract.

“How are you doing?” I asked, as we waited for him to be called to the stand. “I’m shitting myself,” George said with a nervous smile.

After months of tabloid shots across the bow, it had come down to this. Were he to win, George would have done something no other artist had been able to do. Lose, and he was just … done.

“Anything I can get you?” I offered.

“Yeah,” he replied. “A fifth of Jack Daniel’s for the witness stand.”

For some, the headline was: “Ungrateful Multimillionaire Superstar Raged Against the Machine and Got His Famous Ass Handed to Him.” They said he got what he deserved. I say he got what he wanted. George Michael, singer, songwriter, producer, arranger, performer, philanthropist, son, brother, friend and lover would live on, but George Michael, pop star, was no more. It was a world-class implosion and completely voluntary.

That is the thing that made George different from his contemporaries. He was willing to pay the price of his rebellion. While Prince, with whom I also worked, wrote ‘slave’ on his face, recorded furiously and changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol, in part, to escape his Warner Bros. Records contract, George retreated. He wouldn’t tour again for 17 years and would record new material only sporadically. Fences with Sony were eventually mended, for the sake of greatest hits packages, but it was far too late to matter. A large swath of his fans had been either alienated or bored or moved on to the next big thing. The bathroom incident in Beverly Hills kicked the last nail in.

George played the game on the way up but not on the way down. I never asked him why. He was an intensely private person keeping a few big secrets at the time, and I just assumed he’d had enough.

“I’m done chasing it,” he said to me in a candid moment at the time. And he was. The fans ultimately returned for his recent tours, singing back at George from the rafters. The best part was they had come for the only reason that mattered to him: The music.

The first time that I properly met George was when we sang together at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert for AIDS Awareness [at Wembley Stadium in London in 1992]. We’d had the same manager, and I’d said hello to him, but we’d never really sat down and talked before then. It was an unbelievable event. I remember I was in the middle of this rehearsal room with 100 really famous people all around me.

I had no makeup on and I was eating a bacon muffin. George was practicing “Somebody to Love” and he kept on looking at me. I remember thinking, “Am I putting him off?” When I got up to sing “These Are the Days of Our Lives” with him, he said, “How can you eat a full bacon sandwich and then sing like that? I’m so jealous.” It really sticks out as it was the first thing he ever said to me. I had a really good laugh with him.

He was very candid about his own life. A lot of people paint this picture of him as being very precious and, true, he was a very private person, but he was also a really lovely guy. You didn’t feel that there was any malice in him. He got on with his life and tried to do his best. He had demons, but don’t we all?

His music and influence will live on for years and years. When he came out of the closet he helped a lot of other people to think, “F*** it. I’m going to do it as well.” He was quite revolutionary in that sense. It gave liberation to so many gay men and women. The world is a better place for him.

At the time when I wrote “Smooth” with Itaal, I had just gotten off the road with Matchbox Twenty on what turned out to be a three-year-long tour. We started in clubs and ended in arenas all over the world. We were tired.

When I got the call that a writer was working on a track for a new Santana album just around the corner from me, in Soho, I thought ‘what a great chance to work on something for an icon’ not having any real expectation of success.

This was going to be my first time writing a song that I didn’t perform on, setting me up as a writer.

When we finished the song, the conversation came around to who should sing it. I don’t believe I was even in the running. But I WAS in the conversation with Clive Davis and his people about my thoughts on who should.

My first thought was George Michael. In fact, it was George I had in my head when I recorded the vocals in the first place. If you listen to the melody and the cadence, it’s an attempt to emulate his style in so many ways.

The trend carried on. My first solo album was a shift from my Wham! to my Faith. My first solo video had pieces of George all over it. Some of the shots, the close up on the boots, the dance, all of it an homage to someone I had admired since I was a pre teen.

My last album cover for The Great Unknown was a lift from the Wham! Bad Boys video and I didn’t even realize it until after I called the president of Atlantic Records and said that was the pic I wanted on my cover.

It was just ingrained in me.

Because we share the same manager I got the opportunity to spend a fair share of time with George and after my third glass of wine, I would start to gush and he would respond, as he did with everything, like a true gentleman with kind words and insight.

I’ll never be George Michael, but without George, I’m not sure I would have been Rob Thomas either.